Age Is (Still) Not Just a Number

Two questions after last night's debate

(First post on the ages of politicians is at this link—> here.)

“All political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure, because that is the nature of politics and of human affairs.” -Enoch Powell, British politician (1912-1998)

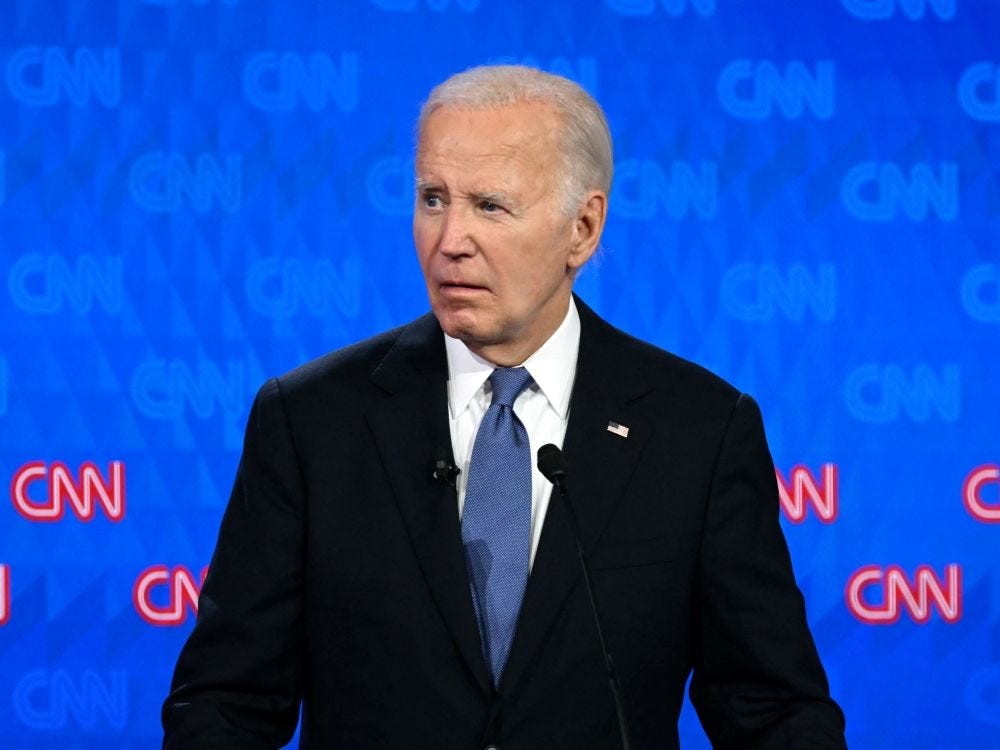

President Joe Biden’s confused, meandering, and enfeebled performance at the presidential debate last night has Democrats panicking. The debate reinforced the most obvious critique of Biden: his age and the effects that has on his mind and body. In liberal circles today, tweet after tweet and column after column are filled with calls for him to drop out and make way for a new Democratic candidate. Some rest the decision squarely on Joe Biden himself—he’s got to decide to give up the party nomination voluntarily. Some write that “the Democrats” need to force him out of the race through a private (and perhaps public) pressure campaign.

Two questions come to my mind.

Will this cause more people to re-think formal age limits for public office?

I wrote about elderly people in public office a year ago when the focus was on Sen. Dianne Feinstein. Back then, I listed several options, including a constitutional amendment to add an age limit for elective office. North Dakota voters just approved a ballot measure setting an age cap on members of Congress from that state. The measure states no candidate for Congress can be on the ballot if he or she would be 80 or older during the term. The law is probably unconstitutional, but standing rules for court cases would first require an elderly candidate to sue to strike it down. It would be a positive step if more states followed suit, and if that in turn led to a federal constitutional amendment. Donald Trump would be 82 at the end of a second term, and Joe Biden would be 86. Both parties have long benches of electable people in their 40s, 50s, and 60s. Of course, we aren’t going to get an amendment in the next four months, given that the most recent one was ratified in 1992. But maybe after this election, we could get serious and put in age limits for elections starting in 2028. That brings me to the more pressing question for this election . . .

Is an American political party capable of replacing a candidate?

Political parties are organizations, and organizations have leaders that make decisions. For example, the Iowa Democratic Party is a non-profit corporation with an executive director and a board with a chair. It was registered with the State of Iowa as business number 76250 on February 19, 1944. It feeds into the Democratic National Committee, which has its own set of formal and informal leaders. A core function of an organization is to make decisions about its mission: who leads it, who represents it, what its brand is, and what its products are. For a political party, its products are the candidates, and the voters are the consumers. When a product isn’t selling, company management can switch up the marketing or pull the product in favor of another. Chevrolet just ended production of the Camaro, a classic muscle car it has produced since 1966. It will likely replace the Camaro with a new electric car. Google had a disastrous roll-out of its Gemini artificial intelligence tool earlier this year, and company management shelved the product until they can fix it.

But, despite some legal formalities, political parties are not exactly like a company selling widgets. Neither the Democratic nor the Republican parties have a CEO (or even a board or council) who can act on his or her judgment and analysis the way that other organizations have. Sure, they could switch up the marketing strategy: they could hire consultants who would make better advertisements for the campaign and pay an army of social media influencers to promote Joe Biden. But they cannot change what people see with their own eyes: Joe Biden is too old. The Camaro isn’t selling anymore. We will see if they are able to do what companies do with aging, sputtering, or poor-performing products all the time: pull it from the shelves.

This, by the way, is what happens with other political parties. I’m about to go to Canada tomorrow, where unpopular Prime Minister Justin Trudeau could be forced by his Liberal Party colleagues to give way to a new prime minister sometime before elections next year. The United Kingdom is having an election next week. Over the 14 years the Conservative Party has been in power, its elected members of Parliament have forced not one, not two, but three prime ministers (Theresa May, Boris Johnson, and Liz Truss) to stand down and not to fight the next election as party leader and prime ministerial candidate. And I won’t even begin to get into the knife-wielding and defenestrations in the Australian Liberal Party and Labor Party. They make Game of Thrones look like a documentary down under. This even happened in the United States once, when a collection of conservative Republican senators went to Richard Nixon in August 1974 and said it was time for him to go, or else they would vote to remove him from office after impeachment. I recognize the mechanics and circumstances of these examples are different and Joe Biden has not done anything nearly as bad as Watergate.1 But Democrats have been saying for years democracy is on the line. That sounds pretty important.

This issue—why don’t “the Democrats” just do this or that—is the subject of a fantastic book titled The Hollow Parties: the Many Pasts and Disordered Present of American Political Parties by Daniel Schlozman and Sam Rosenfeld. They describe how, beginning after the 1968 Democratic National Convention, leaders in both parties ceded their power to pick candidates and direct campaign resources to primary election voters, outside groups focused on single issues, the news media, and donors. There is probably no group of “the Democrats” who could decide something like replacing a candidate for president. Power within the party is diffuse by design. That hamstrings action of the kind most organizations can take when go-to-market plans go awry. Maybe Democratic leaders—elected officials, candidates, DNC members, state party chairs—can convince Biden not to run. Maybe they can force him out through the formal processes at the convention—primary voters and non-party pressure groups and donors be damned. And maybe they can come out in favor of a new candidate and avoid an embarrassing nomination battle in public. But I have my doubts.

Modern-day Republicans—in the Republican National Committee and in Congress—have had several chances on this with Donald Trump: after the Access Hollywood tape in 2016, his first impeachment in 2019-2020 (after extorting Ukraine), his second impeachment in 2021 (after the January 6 insurrection), and his recent convictions and upcoming trials. The GOP’s leaders are clearly not going to remove him.

Agree that the parties are too weak and the current primary system is not generating the best candidates. We need to bring back the smoke filled rooms!

Also, sad about the Camaro. That was my first car!