Can a Third Party Candidate Win the Presidency?

A tale of trying to make "fetch" happen.

Thanks for sticking with me. I took a long break from this blog to focus on local elections here in Des Moines last year. That went right into the holidays and end of the year. Now we are past all that, plus the first few presidential nomination contests, we are looking at another presidential election.

It looks like it will be Biden vs. Trump. Again. Polls show a solid majority of Americans do not want a rematch. Neither man is popular with voters.

A family member recently asked me why, given that dynamic, a third party candidate could not get elected president. I’ve heard this over and over from people I know who aren’t super invested in either party: “I just wish there were a third option,” or “I don’t get why there are only two choices.” It’s a fair question and even fairer desire. I want to sketch out why the next president (and the one after that, and the one after that) will be either the nominee of the Democratic Party or the nominee of the Republican Party. Why is a “reasonable third party option” not riding in like a white knight to rescue us? There are four steps to this.

1. Dissatisfied voters are divided.

The easiest answer that doesn’t get into our electoral system itself is this: the people who are dissatisfied with Biden and Trump (or Democrats and Republicans, generally) don’t agree with each other. Consider the type of people who are fed up with the two parties:

Progressives and leftists. These people would prefer that Bernie Sanders, or someone like him, be president.

Self-described “moderates” who are socially liberal and economically centrist. These are people who are generally OK with things like gay rights, abortion rights, healthy levels of immigration, free trade, and aid to Ukraine. They also don’t really want to rock the boat too much on taxes, healthcare spending, etc. Maybe the preference here would be an uncharismatic billionaire like Michael Bloomberg or former Starbucks CEO Howard Schulz. If you’re reading this, you’re probably a college-educated person and think this is the true middle, the obvious why-can’t-we-all-just-agree middle ground. But this group is much smaller than the next group.

Populists. These people are in some ways the inverse of the prior group. They probably support a universal healthcare system, higher Social Security payments, higher taxes on rich people, etc. They would also support economic protectionism, Trump-style immigration policies, and isolationism in foreign affairs. Unclear who this group would support.

Anti-Trump conservatives. These are people who are on the right on pretty much every political and cultural issue, but despise Trump. They would prefer someone like Liz Cheney or Mitt Romney as president.

Libertarians. Pro-weed, pro-choice, pro-gun, anti-regulation, anti-tax. Live free or die.

Kooks. Anti-vaxxers, flat-earthers, and other people who the rest of us wish had never gotten the Internet. There’s a sprinkling of these people throughout all the other groups.

If these people coalesced into one party, what would it stand for? For and against abortion rights, for and against aid to Ukraine, for and against a full-scale immigration crackdown—the list goes on. These people say a “plague o’ both your houses,” but they don’t agree—at all—on what the third house should be. You could point out that in the 20th century, the two major parties used to have liberal and conservative wings. They were often culturally and ideologically incoherent. Segregationists and urban liberals in the Democratic Party? New England WASPs and libertarian ranchers in the Republican Party? But, the parties back then also had their own histories, regional strengths, and class-based appeals that this mythical third party doesn’t have.

OK, but let’s assume that, somehow, a third party or independent candidate unites a critical mass of people fed up with Biden and Trump. How hard is it going to be to win the White House? Let’s jump into the system.

2. Single-winner elections usually come down to two people.

When an election has a single winner, the tendency is for the race to come down to two candidates. Hiring a new employee often has the same dynamic—this person or that one. Most people whose first choice would probably be a third or fourth party option end up voting for one of the major candidates to avoid “wasting” their votes on someone who probably won’t win. The perception of electability becomes a self-fulfilling (and self-defeating) prophecy for third party supporters. French political scientist Maurice Duverger summed this up in 1954 and his thesis is known as Duverger’s Law. Countries that have single-winner elections tend to have fewer parties than countries with multiple-winner elections.

In the US, all major offices are single-winner elections. We elect one president, one governor, one US senator at a time, one US representative, one state senator, one state representative, one mayor, and so on. It’s a well-established habit for us. Most countries have some form of multi-winner, proportional representation system, but we generally do not. For many of us, we are used to holding our noses and voting for the lesser of two evils, because we don’t want the other party to win. That habit is deeply ingrained and it’s hard to break. The prevalence of single-winner elections combined with Duverger’s Law is a big reason for that.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume again that Americans overcome this. Pretend that tens of millions of us are truly ready to shed the habit of voting for one of the two major parties and declare “Duverger be damned!” So, are we going to elect a third party candidate?

Well, that candidate is going to need a campaign organization. That organization has to be built to compete.

3. Barriers to entry are high.

Economics has a concept called “barriers to entry.” These are obstacles that make it more difficult for a business to break into a given market to compete. Even if current market participants are susceptible to competition and disruption because of bad practices, lack of innovation, and stagnation, they can still remain dominant because entering the market is so difficult for new challengers. A political candidate or a new political party is no different.

You might think running a successful political campaign is like opening up a new lunch spot downtown. You’ve got to register your business, probably get a small business loan, get a lease, buy equipment and ingredients, hire workers, pass health inspections, etc. It would be a lot of work, but it’s possible to get a thriving business up and going in short order. The barriers to entry aren’t nothing, but they’re not that high. So restaurants come and go. Compare that with building a company to take on the commercial jet duopoly dominated by Boeing and Airbus. You would need billions of dollars, world-class engineers and manufacturing experts (almost all of whom work for Boeing and Airbus), experienced pilots and mechanics who train on your aircraft, relationships with air travel regulators around the world, and purchase agreements with major airlines. So even though Boeing has some pretty well known problems, taking them on is not something some amateur could do. The big boys are—and I’m deeply sorry for this pun—flying high.

To win a presidential election in the US, you need a few things: a nationwide army of volunteers, competent and professional staff who know how to win (and who probably work for Democrats and Republicans now), clever and effective advertisements and marketing, and plenty of media coverage. Oh, and lest I forget: you’ll need lots and lots of money. (A vision for the country and demonstrable leadership skills are nice to have, but kind of optional.) The centrist group No Labels aimed to raise $70 million for a possible third party challenge this year, which is an impressive sum. But that’s a little over 1% of the $5.7 billion total amount that the campaigns, parties, PACs, and other groups spent on the last presidential election. The race for Congress, in which every winner was a Democrat or Republican, was another $8.7 billion on top.

These aren’t sandwich-shop-on-Main-Street barriers to entry. These are take-on-Boeing-and-Airbus-from-scratch barriers to entry. But, let’s assume our third party challenger has cleared all these hurdles. The disaffected voters have united around one quasi-centrist candidate. They convinced each other to quit voting for the two major parties. The candidate has a legitimate organization with sufficient resources behind it. On to victory?

Not so fast. An old friend from Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution is waiting with one last bucket of cold water to dump on you.

4. Electoral College makes winning really hard.

For a third party candidate to win, it’s not enough just to get a lot of votes. That candidate could even get the most votes nationwide and still lose—just ask Al Gore and Hillary Clinton. A winning candidate has to win the popular vote in individual states to win electoral votes in the Electoral College. Those votes then have to add up to a majority of at least 270.1

The problem is a bunch of states are a lock for Republicans, and a bunch of states are a lock for Democrats. That would be true even if we had a true three-way race. Let’s look at 2020. In that year, 20 states had margins of victory for Biden and Trump of 20% or greater. These were landslide states like Wyoming, Tennessee, Vermont, and California. Those states are off the table for a centrist third party candidate—they are just too strong for one of the main parties for an upstart to run up the middle. If Trump got 65% of the vote in a state for a two-way race, a well-funded centrist third party could knock him down a bit—maybe even under 50%. But that would probably not be enough to win a three-way race in that state. And if a candidate doesn’t come first, that’s zero electoral votes. Write them off.

The remaining states, where the margin of victory was between 0% and 20%, had 346 electoral votes up for grabs in 2020. To get to 270, that means a third party candidate would have had to win 78% of the remaining electoral votes. That probably means sweeping all the true swing states like Georgia, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. It also would probably mean picking off nearly all the bigger states in the next tier, like Virginia, Florida, and Texas. That kind of record in a three-way race (or even a two-way race) would be astounding. And, again, this is to beat two political parties that, between them, haven’t lost a presidential election since 1848, when the Whig Party(!) ticket of Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore won.2 Good luck!

The last election wasn’t really an anomaly either. That stat I just shared where a third party would have to win 78% of the electoral votes in the non-landslide states? It would have been 77% in 2016, 77% in 2012, and 76% in 2008.

Or, just consider the long history of third party challenges. No third party candidate has ever gotten close a majority of electoral votes. Consider the top three third party challengers since the Democrat-Republican duopoly came into being in 1852:

1860 - John C. Breckinridge, Southern Democratic Party (24% of electoral votes)

1912 - Theodore Roosevelt, Progressive Party (17% of electoral votes)

1860 - John Bell, Constitutional Union Party (13% of electoral votes)

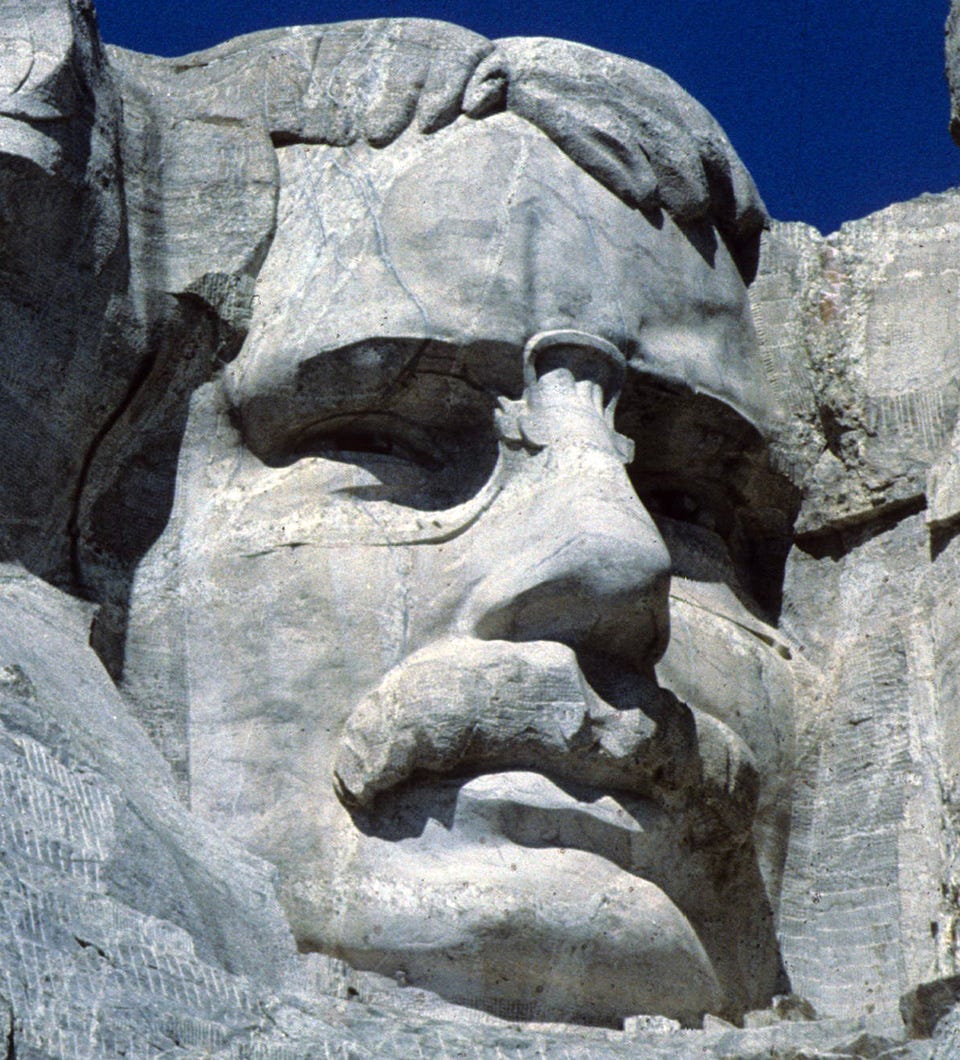

In other words, the people who have done the best are a man who had already been president for eight years and whose face is on Mount Rushmore, and two men who ran in the year Abraham Lincoln didn’t appear on the ballot in half the states and the nation literally split apart and descended into war over slavery. A third party winner is just not going to happen.

More cold water than the ALS ice bucket challenge

I know this isn’t uplifting if you want a third option who can win. But that’s the full answer. The people who don’t want Biden or Trump wouldn’t be able to agree on a candidate. Single-winner elections tend to narrow to two candidates, and Americans are just not used to voting for someone who isn’t a Democrat or Republican—even if most Americans don’t like either party. The cost, expertise, and organization to run a competent campaign would incredibly hard to pull off. And to top it off, the Electoral College plus the existing dominance of one party in many states makes the math damn-near insurmountable.

For someone who isn’t a Democrat or Republican to win—or even have a fighting chance—we would probably need to reverse all this. We would need to get Americans used to voting for third parties in multi-winner systems for other offices. We would need to drastically reduce the cost of running for office. And we would need to repeal the Electoral College and use the national popular vote for presidential elections. Until then, a third party candidate would have to run a tightrope across the Grand Canyon on a windy day. Any takers?

Yes, it’s possible to throw the election to the House if no one has a majority. But, unless a third party has the largest number of seats, the winner is still going to be one of the main parties.

This example doesn’t really count either, since the Republican Party hadn’t been founded yet. I just wanted to drop a Millard Fillmore reference. Shout-out to Millard.

I agree with your analysis. The only chance would be to have some beloved celebrity (Tom Hanks?) that might drive enough interest across party lines. Think Jesse the Body for MN governor. Ballot access still an issue unless No Labels lays the groundwork this year.